Growing up, my sense of fairness came from two things. The first is sports. My dad was a coach. He coached football, basketball, and track during the school year and gave swimming lessons in the summer. I grew up in small towns in central Illinois – Lincoln, Gibson City, Kankakee – and then we moved to the big city of Peoria where my dad was the athletic director at the new Richwoods High School. The year was 1956. My dad believed in the fairness of sports and the value of everyone participating in physical activity. He made sure the new high school had a swimming pool and that all students took swimming classes, including students with disabilities. He was competitive, but he cared more about everyone playing and playing fairly.

A coach’s son is expected to play sports, and I did. I loved sports and played basketball and tennis for both Duke and Depauw, the two colleges where I split my undergraduate years. Later, I worked as a tennis teacher and coached Johns Hopkins University men’s tennis team. I loved that with each new game or match you started off fresh; the “playing field” was level. It’s assumed that talent will determine the outcome, and that the rules – with a referee or not – reinforce fairness.

The second thing that influenced my sense of fairness was belief in this country’s founding documents. As I grew up and read our Declaration of Independence and Constitution – “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all…;” “We the people of the United States, in order to…” – the words made sense to me. I thought the ideals reflected in those documents were the way life was. At some level I knew these were ideals that we needed to live up to, but they fit well with what I grew up experiencing in sports. The better teams won. We started off even and had a fair chance at winning. At fulfilling the dream. Maybe in an athletic contest, maybe in life.

A parent’s most challenging task may well be simultaneously instilling the ideal of fairness in their children and teaching them the reality of inequity in America. We want our kids to believe in the values embedded in our country’s founding documents. But then again, when Jefferson wrote that “all men are created equal,” our country didn’t come close to living up to that ideal.

When raising children, it’s essential to explain that we as a country have always struggled toward our better nature, but that we’ve never stopped striving. That begins with teaching and learning not only about our founding documents, but our history of slavery, destruction of native peoples’ cultures, and Jim Crow. And part of that lesson is that not all of these inequities are comfortably relegated to the past. The legacy of how we have treated each other and organized our economy is woven into our current institutions, including many that affect health.

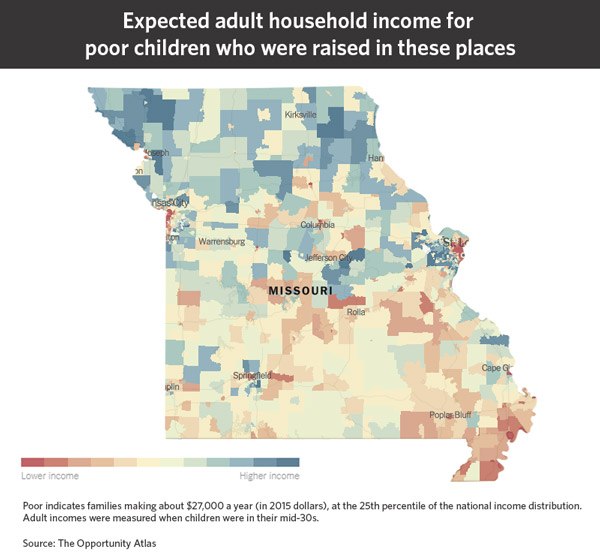

In health, the reality of inequity is pervasive. Extensive data and research documents health disparities by race and ethnicity nationally, in Missouri, in our counties, and ZIP codes. Strong evidence shows similar results for underlying determinants of health such as housing and income. Governmental legal institutions have systematically reinforced racial and ethnic inequities. In brief, we have fallen far short of living up to our ideals – the promise of our unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Growing up and learning about the lack of fairness, including the privilege that I had growing up as a white boy when and where I did (in a middle-class family at a time of growing prosperity and far greater economic equity than today), was quite sobering. In fact, I still consider it a work in progress. I continue to reflect on the two formative influences on my sense of fairness: sports and the ideals espoused by our Founding Fathers. I still look to our founding documents for inspiration about the fairness our communities and our country can achieve. However, my sports metaphor for fairness hasn’t aged quite as well. In the real world we don’t start with a level playing field. Every adult knows this, even as we rightly espouse fairness as the bedrock of our society.

Growing up and learning about the lack of fairness, including the privilege that I had growing up as a white boy when and where I did (in a middle-class family at a time of growing prosperity and far greater economic equity than today), was quite sobering. In fact, I still consider it a work in progress. I continue to reflect on the two formative influences on my sense of fairness: sports and the ideals espoused by our Founding Fathers. I still look to our founding documents for inspiration about the fairness our communities and our country can achieve. However, my sports metaphor for fairness hasn’t aged quite as well. In the real world we don’t start with a level playing field. Every adult knows this, even as we rightly espouse fairness as the bedrock of our society.

Perhaps this unsettling contradiction is why a player kneeling before the start of a game causes our country such consternation. For that action brings into stark relief the gap that remains to be bridged between the fairness embodied in the game about to begin and the inequity experienced every day by so many Americans in the real world. Fairness is at the heart of how we should treat each other, and how we treat each other has a profound influence on the health of our society. Confronting that distance between our national ideal of fairness and the reality in society and health is a crucial next step to progress for all of us.