Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) more than a decade ago, Missouri Foundation for Health (MFH), along with thousands of advocates across the state, has focused attention and resources on connecting Missourians to health care coverage. These efforts, while ongoing, have been remarkably successful. In 2020, over 70,000 more Missourians had health coverage than in 2010, enhancing access to care, reducing health inequities, and resulting in better health.

The passage of Medicaid expansion through a ballot initiative in 2020 is the final piece of the ACA coverage puzzle in Missouri. Despite a troubled rollout, more than 270,000 Missourians have enrolled in the expansion, further reducing disparities in coverage and health and bringing a flood of state tax dollars back home.

Despite these substantial and important gains, however, health care remains out of reach for many Missourians. More than 9% of the population remains uninsured. And even when people can afford insurance, many cannot afford the care they need. The biggest barrier to care has been – and remains – high health care costs.

By now, the statistics are familiar to many of us. The United States has by far the highest health care costs in the world, paying more – without better results – for the same medical procedures and prescription drugs as people in other countries. Residents of Missouri face these same high-cost burdens.

Earlier this year, MFH engaged Altarum Healthcare Value Hub to conduct a Consumer Healthcare Experience State Survey (CHESS) in Missouri. In a poll of more than 1,100 Missouri adults, 62% reported health care affordability burdens in the past 12 months, including being uninsured due to high costs, delaying or going without care due to cost, and struggling to pay health care bills. More than four-in-five (82%) worry about their ability to afford health care in the future.

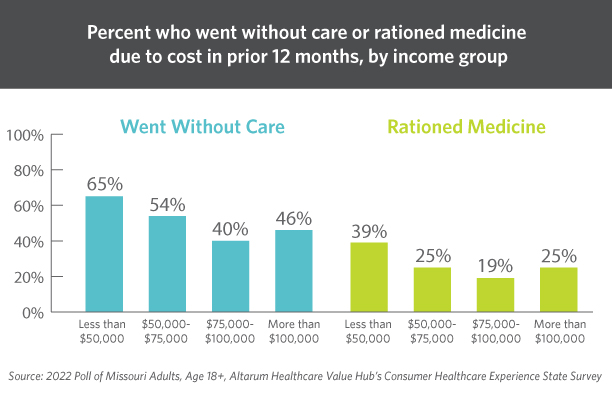

These burdens are not shared equally. Households that include a person living with a disability are far more likely to ration medication, go without care, or go into debt to pay for care than those without a disabled household member. The same is true of lower-income households.

People of color reported slightly higher rates of affordability burdens in this survey than white people, including more problems getting behavioral health and dental care. But cost was not the only factor impacting access to care for people of color: 33% reported skipping needed medical care due to distrust of or feeling disrespected by health care providers, compared to 22% of white respondents.

Altarum has conducted CHESS surveys across the country and the results are strikingly similar everywhere: Americans struggle to afford health care and worry about their ability to afford care in the future. This cuts across party lines. Large majorities of Democrats, Independents, and Republicans believe health care costs are too high and something should be done about it.

Some states are recognizing the need for change and taking action. In three states—Colorado, Washington, and Nevada—a public health insurance option has been implemented to drive down health care costs while offering coverage to state residents. In 2012, Massachusetts became the first state to enact a cost growth benchmarking program, a tool that can be used to provide structure and process for increasing health system transparency and developing strategies for containing costs. Seven other states now follow this practice.

In recent years, the Missouri legislature has passed a few measures aimed at controlling the costs of health care. In 2016, the Missouri Department of Insurance was authorized to disclose insurance rates that it finds unreasonable, creating transparency in the rate-setting process. In 2018, a law was passed protecting consumers from surprise billing when seeking services from an in-network provider for emergency medical conditions. Both of these measures are positive steps towards lower costs.

At MFH, we’re building momentum too. We’ve worked to address the issue of high health care costs and examine solutions in various ways over the last year. In addition to the CHESS surveys, we partnered with Midwest Health Initiative to create a health information blueprint that set the foundation for the development of an all-payer claims database (APCD) in Missouri. APCDs, which have been implemented or are being assessed in more than 20 states, aggregate health care claims and related data from both public and commercial payers, providing a comprehensive view of health care prices and quality. We also held a convening on prescription drug pricing that brought together stakeholders from around the state, including leaders from academia, nonprofits, and advocates to share approaches to drug pricing transparency and insulin cost-sharing that are being tried in Texas and Utah. Projects that look at medical debt and how health systems provide services to Medicare beneficiaries in under-resourced areas are underway.

Solutions are within reach, but more is needed to curb the burden of excessive costs. Given the high level of public support, the message is clear: Missourians want providers, insurers, employers, and elected officials working together to ensure everyone can get the care they need at a price they can afford. MFH is committed to that challenge and will continue to work with state and national partners to contribute to that change.