Organizers Undaunted, Continue Championing for Working People’s Rights

Missourians voted to increase the state minimum wage in 2016, but that got undone by state legislators. Years later, voters affirmed their choice and a requirement for paid sick leave, only to have the Missouri General Assembly undo parts of that measure. But the organizers behind the effort expect to continue the fight.

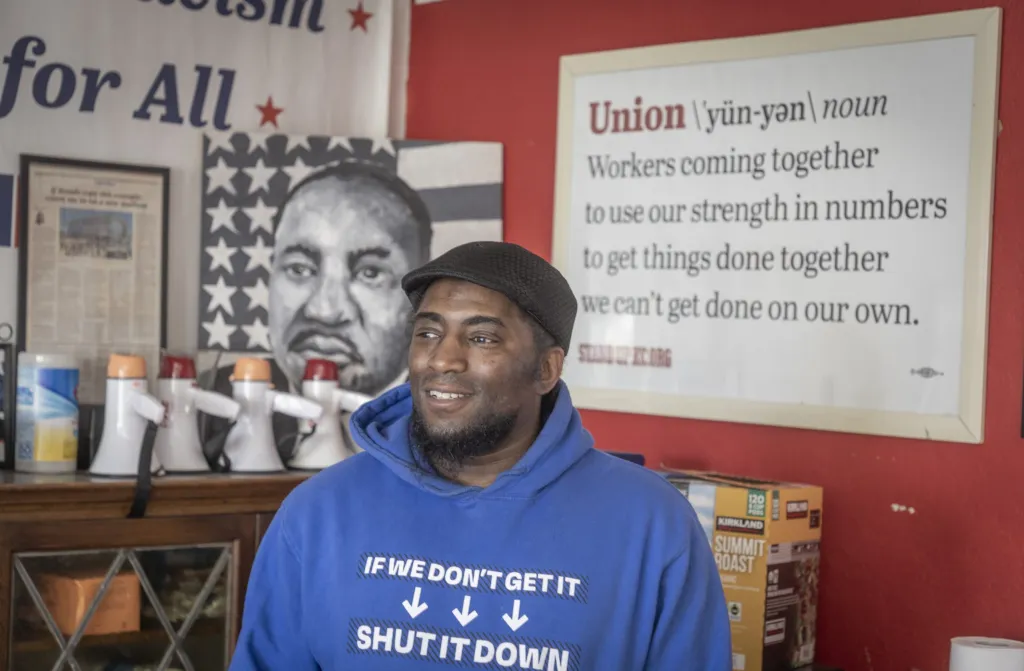

A trio of fast food workers – one each from McDonald’s, Subway and Domino’s – walked into a Burger King and changed Terrence Wise’s life.

At the time, the spring of 2012, Wise was working two jobs: one at Burger King, the other at a Pizza Hut, making $7.25 and $7.47 an hour respectively. He was barely covering his living expenses when those other workers introduced him to a new concept: a living wage.

“They came up to the counter and they were like, ‘Do you think workers deserve a living wage?’ and I was like, ‘Yeah!’ I didn’t know what a living wage was, but I knew ‘living’ and I knew ‘wage.’ I just never heard them together,” he said.

A living wage, Wise quickly learned, was a calculation based on what a full-time worker should make per hour to cover basic needs where they live. The fast-food workers Wise met were also rallying for better benefits, health care coverage and vacation time. Inspired, Wise signed on as an organizer, giving way to the birth of the Missouri Workers Center, a movement made up of low-wage workers whose mission is to apply pressure on management and elected leaders to change everyday labor conditions.

The Workers Center, headquartered in St. Louis, has seen its share of highs and lows. In 2016, it successfully lobbied for a higher minimum wage in Kansas City ($13 per hour by 2020) and St. Louis ($11 per hour by 2018), only to be overridden by state legislators who passed a preemption law in 2017, prohibiting cities from setting a minimum wage higher than the state rate. (That became $13.75 in 2025, but back in 2017 the minimum wage was roughly half that amount.)

The law quickly nullified the labor’s victory. It also meant that some hourly workers in those cities actually saw their wages decrease. One woman told NPR reporters in 2017 that her wages shrank from $10 an hour to $7.70.

For Wise, it was bittersweet.

“It was really hard that day. The only solace I’ve taken is that it still felt good to be in the ring. For many years we were just taking the punches, and decisions like preemption were being made without me having a voice. So I did feel good about … taking that blow fighting in the moment,” he said.

Stymied by lawmakers, the workers group looked for a workaround and became a part of a coalition that found a solution in the initiative and referendum process.

The center leaned hard into leveraging worker power, sending hundreds of its advocates to get familiar with their fellow Missourians. Groups came to realize that voters were friendlier to their cause than the General Assembly, so they chose direct democracy as a strategy. As inspiration, the center pointed to Colorado voters overturning a similar preemption law in 2019.

Like Colorado, Missouri is one of 24 states with an initiative process, which allows residents to bypass their state legislature by placing laws, and in some cases constitutional amendments, on the ballot, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Once again, the Missouri worker advocates succeeded. Proposition A, containing a $15 minimum wage by 2026 and up to seven days of paid sick leave made it to the ballot in 2024, and passed with nearly 58% of Missourians voting in favor of it.

The increase started on January 1, raising the floor to $13.75, which impacted nearly 440,000 working people.

“In Missouri, the voters have never seemed to back down from protecting workers’ rights. That’s why the ballot initiative is so extremely important,” said Gina Chiala, the executive director of the Heartland Center for Jobs and Freedom. “We’ve seen in the past that voters consistently increase the minimum wage when they’re given an opportunity to do it. I think it’s going to drive a lot of working people and people who care about human rights to the polls.”

But what’s happened since shows the limits of direct democracy. What voters can deliver, elected representatives in the Missouri legislature can overturn. Interest groups that opposed Prop A also unsuccessfully turned to the courts, challenging the measure on procedural grounds.

According to the Missouri Independent, Senate Republicans used a rarely invoked procedural maneuver to cut off debate and pass bills involving two voter-approved initiatives: one protecting abortion rights and another increasing access to paid sick leave. They also repealed a portion of Proposition A’s minimum wage increase, which is based off of future hikes on the consumer price Index beginning in 2027.

Missouri Gov. Mike Kehoe signed the sick leave repeal in early July. Missouri workers that began accruing paid sick leave in May will lose it August 28.

The minimum wage will still increase to $15 per hour in 2026 but no increases will take effect beyond that.

Byron Keelin, president of Freedom Principle MO, said his group was one of the few organizations that had been lobbying against Prop A since the fall. He is skeptical of the intent and origins of the ballot initiative, saying that urban lobbyists and voters were over-represented.

“The other issue here is that Missouri’s economy is predominantly a rural economy. We have some urban areas but the majority of these businesses are small mom-and-pop businesses in rural Missouri that don’t have the resources to pay $15 an hour or pay paid time off,” he said. “We’re talking about the fact that minimum wage is meant to be an entry wage. It’s not meant to be a living wage. It never was.”

Yet an analysis of last fall’s vote suggests that Proposition A’s popularity did transcend the urban-rural divide to some degree. Prop A won with 61% of the vote in 12 of the 23 jurisdictions in which proponents collected more than 500 valid signatures. It also won 12 of the 93 jurisdictions where Prop A gained fewer than 500 petition signatures. Yet it still carried about 50% of the vote in those areas.

“Prop A got more votes (1,693,064) than Sen. Josh Hawley (1,651,907), with more than 400,000 voters splitting their vote for Hawley and Prop A,” a spokesperson for the Missouri Workers Center wrote in response to questions.

The spokesperson also pointed out that 500 Missouri businesses endorsed the measure, mentioning research that shows Missouri’s unemployment rate went down faster than the national average – more than any neighboring state that didn’t increase the minimum wage.

Parts of southwest Missouri, where grants funds had supported low-wage warehouse worker organizing, emerged as a particular area of strength for Proposition A. Greene County, where Springfield is the county seat, contributed 14,239 valid signatures to the ballot petition, the most of any county outside the St. Louis and Kansas City regions. Prop A won the county with 55% of the vote. Jasper County contributed 3,925 valid signatures and Prop A narrowly lost there, 51%-49%.

The region’s 14 counties contributed 15% of the ballot measure’s valid signatures. Prop A won two of those counties outright and carried 48% of the vote across them.

There’s evidence that supporters of Proposition A could revive the paid sick leave law by asking voters to approve it as a constitutional amendment. KCUR-FM, the Kansas City NPR affiliate, reported that Missouri Jobs with Justice, a coalition that has included the workers center, has filed a proposed amendment targeting the 2026 ballot. The Missouri Workers Center hasn’t said explicitly in response to questions if it plans to continue its push at the ballot box.

But individuals like Wise aren’t giving up.

“It’s a never-ending fight. You not only got to fight to win these things, but fight to keep them. I’ve come to realize this: We’ll never not be fighting,” he said. “We have to keep strengthening whatever our victories are. There’s always going to be opposition. Can you get weary? Of course. But we simply won’t go away.”

Wise said that one advantage working people can use in their advocacy is amplifying labor issues via a community lens, not a political one.

“I never approached anyone in my circle or while organizing and said, ‘Well, that must be a Democrat, or that must be Republican, so they only care about this or that,’” he said. “I ask questions about the workplace, family, community, and that’s how we come together. We as Americans should ask the questions: Is my family worth more? Is my community worth more?”

“We all go up or we go down together“

Unions, too, are democratically organized, with members voting to elect leaders that have the goal of making workplaces safer and better. According to the AFL-CIO, the largest federation of unions in the country, unionized workers make $191 more per week than their nonunion counterparts and are more likely to have employer-provided pensions and health insurance.

Chiala said there are specific challenges faced by low-wage workers that go beyond what’s in a paycheck: wage theft, discrimination and eviction risks due to a lack of paid sick leave and restrictive shift schedules.

According to the National Low income Housing Coalition, a minimum-wage Missouri worker (at the state’s 2024 level, which was $12.30 an hour) would need to work at least 55 hours a week to afford a modest one-bedroom apartment.

“This is why housing and workplace issues go hand in hand,” Chiala said. “If you don’t get paid sick days and you get COVID and miss a week of work … you’re already living paycheck to paycheck. Not having paid sick days puts people in the crosshairs of eviction.”

Ash Judd, an Amazon warehouse worker in St. Louis, said he was hurt – mentally and physically – by the state’s preemption law.

“Preemption is hurting workers like me who just want to leave work in the same condition we arrived at it,” he said in a virtual news briefing just before the Senate vote. “I was surprised by the toll working at Amazon took on me. I didn’t expect to be sore the way that I was after those long shifts. I have hip and joint problems now that I don’t think I would’ve had otherwise.”

Wise and the Workers Center emphasize that fast food, retail and shipping jobs often lack rest or water breaks and are prone to workplace injuries and high stress, which sap an employee’s well-being — and destabilize the workforce.

“We all go up or we go down together,” Wise said. “I think of the worker that got that raise on January 1, and it moved their dollar amount up, but it also improved the wages of the worker making slightly more than them.”

Wise, who currently works as a driver with Uber, DoorDash and Instacart, was delighted to see his base wage as a gig worker tick up from $2.50 to $4. He said his daughter, who works for a telecommunications company, saw a $2 raise at her job. Wise’s sister, working at a McDonald’s, went from $13 an hour to $15.

Workers who make low wages may shy away from organizing, fearful that any involvement could result in a job loss. This is a fear that organizations like the Missouri Workers Center and the Heartland Center for Jobs and Freedom are used to hearing. Chiala, the executive director for the Heartland Center, said it’s important to educate workers before encouraging them to take action.

“We do know-your-rights workshops. This is the best way for workers to both learn about their legal rights to organize, but also how to really win real change on the job,” she said. “It’s hard to organize for various reasons, partly because of the erosion of labor protections and union rights, so we really need what we call social unionization, meaning workers have the power and leverage to win things from their workplace and employer themselves.”

Chiala thinks there’s less risk for workers who organize for better workplace conditions than those who don’t. Working people who unionize get certain protections, such as being guarded from retaliation.

“If I go by myself to my employer and I say, ‘Hey, I think we should have higher wages. I think we should have a safer workplace,’ you’re at risk for retaliation. That right doesn’t exist. But if you join together with your coworkers, suddenly the employer is not allowed to retaliate against you under the law,” she said.

Labor rights organizations such as the Missouri Workers Center also exist to step in if conflicts arise between a union and management. If an employer attempts to retaliate, then the center can rally the community to vocally opposite management’s actions.

Wise said that he understands the hesitation, but he tries to help others understand the power in the collective. That matters, even when Missouri lawmakers override their efforts.

“I understand that it’s my bosses that control my everyday living conditions. … But if you get workers organized in the workplace, then you can transfer that power,” Wise said. He added that the Workers Center has been successful in recruiting low-wage workers to their cause by emphasizing the potential impact on their quality of life and families.

“Folks are busy. They work hard. They’re trying to survive. It’s hard to get a reason to want to stand up, go vote, go fight back, go knock on doors,” he said.

“But if you ask anyone: If someone attacks someone you love, what are you going to do? Just stand there and take it? One hundred percent of folks will say they’re going to fight back. Well, that’s what these corporations and even legislation does. It may not come and punch you in the face, but it attacks your kids, your family and communities. What are you going to do about it?”

Chris Green, executive editor of The Journal, contributed to this story.

This story was produced through the Missouri Solutions Spotlight project, which receives funding from Missouri Foundation for Health. Articles for this project were developed by regional journalists working independently of the Foundation and supported by the staff of The Journal, a solutions-oriented nonprofit news outlet based at the Kansas Leadership Center. The Foundation had no editorial involvement, including no control over the selection, focus of stories or the editing process of Missouri Solutions Spotlight. Funders also do not review stories before publication.

You can view the original stories here. Slight modifications were made to this story by Missouri Foundation for Health to ensure alignment with brand standards.