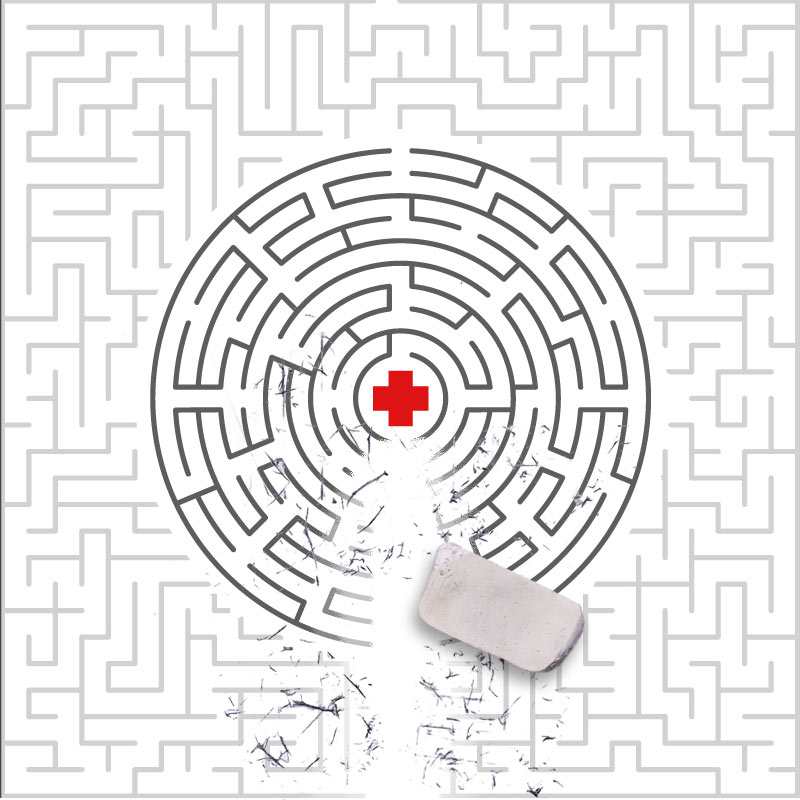

Missouri’s health and social safety nets were hanging by a thread even before the pandemic. This is nothing new. Nursing and doctor shortages result in longer wait times and delayed care for patients. Lack of coordinated care prevents patients’ needs from being comprehensively considered. Other factors that affect one’s health, like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood environment, and employment are not always considered as part of a patient’s plan of care. Addressing these shortcomings and others begins with innovative thinking around new care models.

In 2017 Missouri Foundation for Health started to explore experimental ways to help people get care where and when they needed it. Through the Access to Care initiative, we partnered with organizations from around the state to improve how providers could best serve patients. Across these efforts, we’ve found several successful strategies that are reinventing service delivery.

- Enhance collaboration across sectors to address the social, physical, and economic conditions impacting health. Social and community services are often disconnected from medical services and public health programs. To improve integration, some organizations promoted cross-sector coordination. In the Bootheel, for example, regional health departments and a local family support program shared office space, allowing families to connect to resources more easily. Previously, clients would have spent significant time contacting individual agencies to get the help they needed. Now, the co-location structure offers one-stop access to services such as assistance to apply for Medicaid and SNAP, child development assessments, transportation, and prescription medication.

As the pandemic further strained families’ abilities to afford basic needs, one federally qualified health center added a food security assessment to the intake process for those diagnosed with hypertension. Partnering with a local food bank, patients received groceries, dietician consultations, and cooking demonstration classes.

Lastly, changes at the organizational level, such as the adoption of a standard assessment to address issues like employment, transportation, and food insecurity, was a promising strategy that partners found easy to implement.

- Expand roles of health care professionals to meet the needs of patients. Provider shortages and pandemic burnout have put stress on the health care system and availability of services. To fill gaps, organizations have changed the scope of practice of their workforce to safely expand job responsibilities. Many of our partners have hired community health workers (CHWs) to provide culturally appropriate health education information, advocate for individual health needs, and help people navigate services. With the addition of CHWs, more patients have been following their treatment plans and communication between patients and doctors has improved.

In places where there aren’t enough doctors, patients are usually forced to travel long distances or forgo care. To increase the pool of providers in its community, one agency worked to grow the role of nurse practitioners to meet patients’ primary care needs. In doing this, nurses built trust and confidence with patients as they stepped into a lead role in coordinating and managing patients’ care.

Pharmacists have also expanded their roles, and the results are promising. At a federally qualified health center, pharmacists assisted patients with hypertension by providing one-on-one education and guidance on prescriptions and self-monitoring techniques. As a result of these efforts, patients have reduced their blood pressure, increased their knowledge of hypertension prevention and treatment protocols, and improved adherence to their prescription regimen.

- Centralize and share client information across providers. Client data is usually siloed and inaccessible between health and social service organizations. To eliminate these barriers, several organizations established central repositories to document referrals, needs, and services. For example, in Northeast Missouri partners implemented a Community CareLink system to share client assessment data on health and social needs and make and track referrals. Over the last few years, there has been an increase in the number of partners who have used the system, which has led to improved client connections to local social service agencies.

- Normalize and continue the use of virtual visits to reduce access to care hurdles. Inconsistent or unreliable transportation has always had a significant impact on patients’ ability to receive in-person care. Then with the disruptions caused by COVID, many organizations had to overcome new social distancing limitations too. With flexible telehealth regulations brought on by the pandemic, virtual visits quickly became a sensible solution.

Community health workers at one organization used computers and phones to provide health education, care coordination, outreach, coaching, and support. Because of the updated telehealth laws, they reached different populations who were not able to access care as easily before the changes. Given some of the initial successes experienced during the public health emergency, many organizations have integrated virtual options as part of their standard approach.

The fact that barriers to optimal health have long plagued delivery systems is a clear signal that change was needed. The pandemic showed us how threadbare our safety net is but also provided opportunities for organizations to pivot and weave together patient-centered solutions, strengthening our health care and social service systems and improving the well-being of Missourians. With the expansion of Medicaid and the anticipated American Rescue Plan Act funding, organizations should build on this momentum and continue to discover new ways to enhance access to care and put patients first.