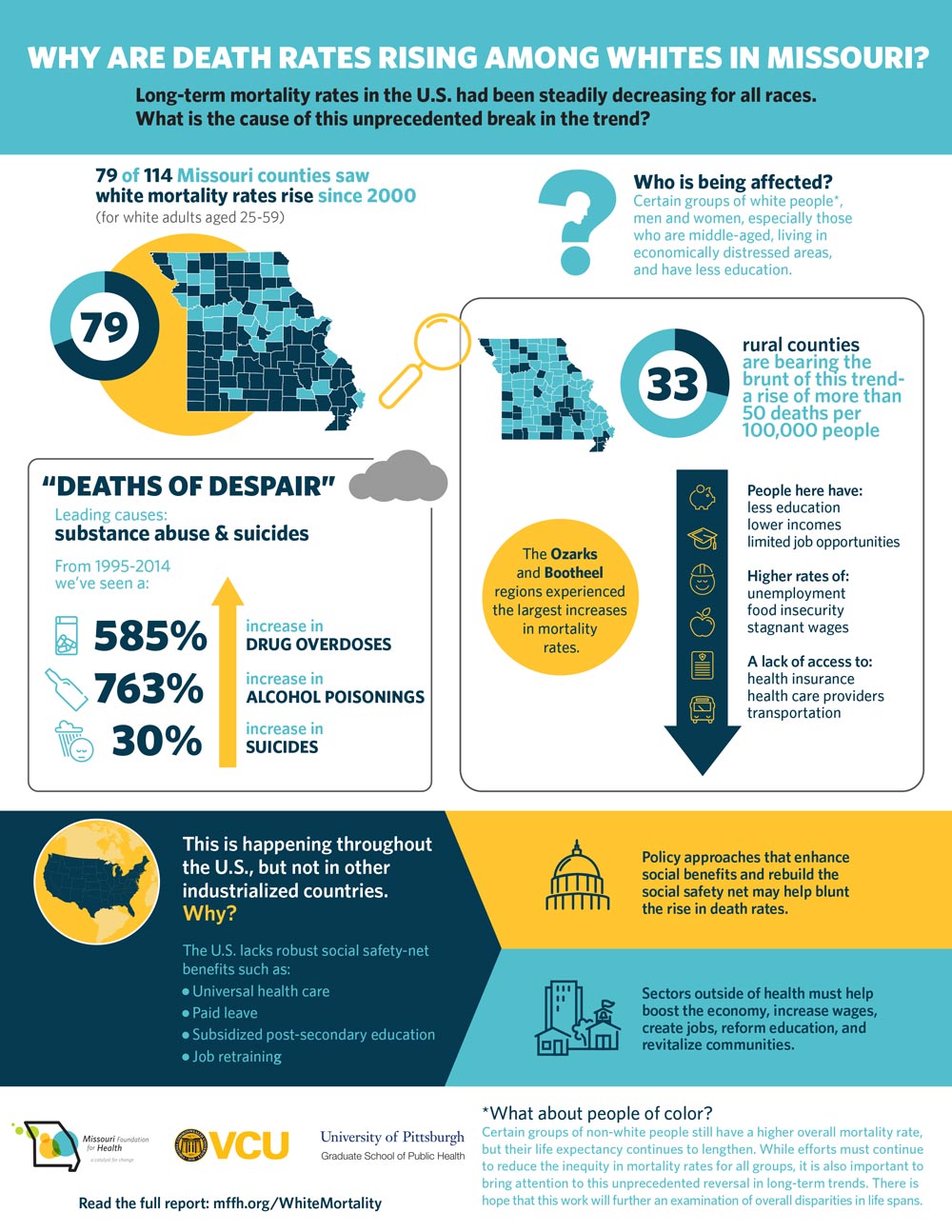

A new report titled “Why Are Death Rates Rising Among Whites in Missouri?” has put the spotlight on a disturbing trend in life expectancies in the state. Since the year 2000, 79 of 114 Missouri counties have seen a rise in white mortality rates for those aged 25-59. The publication – released by Missouri Foundation for Health and created in partnership with Virginia Commonwealth University’s Center on Society and Health, and the University of Pittsburgh – examines the trend in detail. The researchers delve into the demographics behind this shift, and offer potential causes and solutions to this troubling issue.

In particular, the researchers cite an alarming increase in what they refer to as “deaths of despair.” These deaths have a variety of causes, but all speak to a feeling of hopelessness and a lack of opportunity. The report describes it as a “crisis of confidence in the American dream.” From 1995-2014, the 79 affected counties saw a 585 percent increase in drug overdoses, 763 percent increase in alcohol poisoning, and a 30 percent increase in suicides.

Thirty-three counties in particular are facing the brunt of this crisis. These rural areas have seen a rise of more than 50 deaths per 100,000 people (aged 25-59). The counties are scattered across Missouri, but the Bootheel and Ozark areas have seen the largest increases. The 33 counties suffer from long-term poverty, unemployment, a lack of health care access, and few opportunities for the future.

The increase in white mortality is a reversal of long-term life-expectancy trends that have been occurring for all ethnicities. The report is careful to note that overall mortality rates are still disproportionally higher for certain groups of people of color. These racial disparities remain a significant issue and demand action, but this does not change the fact that an unprecedented loss of life expectancy for whites is a significant cause for concern.

“In many ways, the report and data only reinforce what we have seen and heard,” explained Ryan Barker, the Foundation’s vice president of Health Policy. “The question before us is: How do we move forward as a state in addressing these issues for all Missourians, whether for African Americans, Latinos, or the white rural working class? These groups have more in common than many would suspect.”

“Seeing life expectancy go down like this after generations of increases should definitely set off some alarms,” said Robert Hughes, president and CEO of Missouri Foundation for Health. “This is a canary in the coalmine that could be a harbinger of poorer health outcomes for the U.S. population as a whole.”

Economic loss and social changes are both cited as significant causes of the increase in white mortality, not just in Missouri but across the country. However, the report notes that other industrialized nations facing similar issues are not experiencing this crisis. “Put simply, our safety net is not catching people like it should,” said Hughes. Universal health care, job retraining, paid leave, and subsidized post-secondary education are all mentioned as strategies to help put Missourians and all Americans back on a path toward living longer, healthier lives.